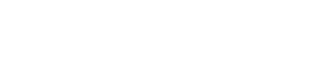

Tucked in a small space between a wall and his mom at Brenham High School, Kaedon Olsen’s shyness takes hold in a crowded room of students and strangers.

In this moment, the usual happy-go-lucky 3-year-old sits hidden. His head, full of curly black hair, occasionally pops up as he stares at his new gift that looks more like a toy than a life-changing device.

As he reaches out to climb on his mom’s lap, the green-and-white contraption hides Kaedon’s deformed right hand. He was born with a rare disorder known as ectrodactlyl syndrome, meaning he’s missing fingers, because they never developed due to a hereditary gene somewhere in his family’s gene pool. Instead, his hand consists of a small partial finger among a mass of flesh and muscle.

But thanks to his mom, a willing teacher and eager students, Kaedon sits with his new prosthetic hand—a custom-made model built by the students in the classroom with the help of a 3D printer that softly hums as it works.

3D printing has been called revolutionary and a game-changer in the medical field with the ways it helps doctors better care for their patients: from preparation for surgeries to building a new hand for a child without one.

Kaedon’s mom, Jeanette, saw an online video about a 3D-printed hand that sparked an idea: What if the same could be done for her son? Jeanette always believed that if Kaedon wanted some type of prosthetic hand, she would leave the decision for him. It’s his body after all, she says. But when an opportunity presented itself, why not ask?

So Jeanette approached Brenham High School computer science teacher Trenton Hall in 2013 when she learned about the school’s 3D printer and inquired about the possibility. She was skeptical, she says, unsure if such a thing could even be done and, if so, would Hall and his class be willing to undertake such a project.

“I thought it would be great to have, but never ever thought it would actually happen for him,” she said.

Hall happily obliged. Through research and hours of Google searches, his students found Enabling the Future, an online organization that specializes in printing 3D hands for people throughout the world. After two months of building and tweaking one of the organization’s designs, Hall’s class gave Kaedon a life-changing gift that December—a wonderful Christmas present, Jeanette says.

“The moment that we gave it to him and we realized this isn’t just a project, this is somebody’s life and opening up possibilities for them,” Hall says, “that was life-changing for us as well.”

Kaedon’s hand is one of six that Hall’s classes created in the past two years—three of which were built for Kaedon as he’s grown from a 1-year-old in diapers to a 3-year-old who loves to hop, skip and dance. Others have gone to children as far as Michigan and Utah.

Another stayed local in Brenham.

Like Kaedon, 9-year-old Ja’Lea Henderson was born without a fully formed right hand, a deformity caused by amniotic band syndrome, a result of string-like bands in the amniotic sac that restrict blood flow during pregnancy. Ja’Lea adapted and learned how to live without a right hand: to tie her shoes, put on her clothes––becoming an independent girl who often refused her parent’s help. She joined cheerleading and dance. She did well in school.

Even overcoming most obstacles she faced, when Hall’s class gifted her a pink and purple arm—her two favorite colors—in October, Kia Nunn saw her daughter’s life change. Ja’Lea is able to pick up objects with both hands. She can count to 10, which has helped her in math. Her handwriting has improved and she can type on a computer.

Hall’s class is hoping to finish its seventh 3D-printed hand, one that’s red and gold and Iron Man themed for a boy in Michigan, in time to be delivered by Christmas.

3Dprinting has grown into a multi-billion dollar industry since it was founded in the 1980s. The technology encompasses various fields from oil and gas to architecture and medicine.

Todd Pietila calls 3D printing a game-changer for the medical industry.

“It’s making personalized medicine a reality,” Pietila says, who works for Materialise, a company that’s specialized in 3D printing since the 1990s.

Back then, 3D printing was largely used for facial reconstruction or dental surgeries, Pietila says. Today, it’s grown to allow doctors to take a patient’s CT scan and create an exact model of the patient’s body part––be it a pelvis, a heart or a brain.

Inside a 25th-floor office overlooking the Texas Medical Center are shelves full of medical books, plaques and pictures of surgeons. Inside one of the cabinets sit models of 3D-printed brains, all with stories to tell.

The office belongs to Dr. David Baskin, a neurosurgeon with Houston Methodist Hospital. Baskin vividly recalls each model as if the patient was sitting in front of him. One model, a dark-blue printed brain, shows an area where a large tumor grew in the back of the brain.

Another, a lighter blue printed version, shows deep valleys and ridges of the brain of an Alzheimer’s patient.

With those 3D models, Baskin says, doctors can better explain to patients what they’re experiencing, how they’re going to prepare for surgeries and perform those surgeries more efficiently.

It’s that kind of access that Baskin says is revolutionizing the medical field.

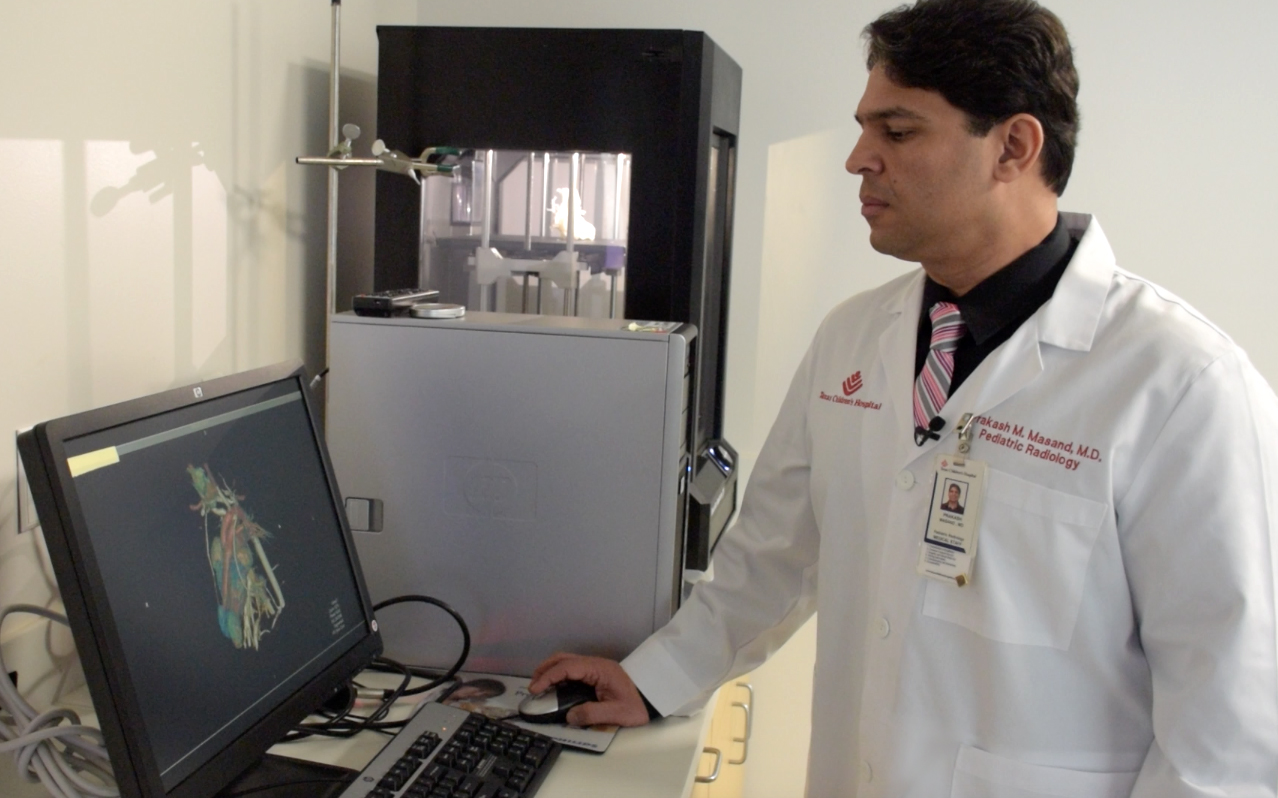

Down the road at Texas Children’s Hospital, Dr. Prakash Masand sits in the hospital’s 3D lab. Masand, the division chief of cardiac imaging in the department of radiology at Texas Children’s, points to 3D models of a pelvis, hearts and child’s chest cavity. Like Baskin, pediatric surgeons are taking advantage of 3D printing technology.

“The big difference in having a 3D-printed model in your hand versus a 3D picture on the computer is this is something you can look at all the angles,” Masand says.

Angles that may not be caught by CT scans or problems that may hide within.

In a case of conjoined twins Knatalye and Adeline Mata, doctors at Texas Children’s Hospital used a 3D-printed model of their chest cavity prior to their separation surgery to get a better understanding of the surgery and its complications.

Pietila, with Materialise, expects 3D printing to continue to flourish in the medical field as more evidence is published proving the clinical and economic benefits of the technology.

Already, Pietila says, there are companies, such as Materialise, that are printing surgical guides and implants that are used in joint-replacement and reconstructive surgeries. Some companies are experimenting with 3D-printed materials that the body can eventually absorb and act as a replacement to tissues and organs.

Pietila says that’s the future, though many of the latest advancements still need to be approved by regulatory agencies, such as the Food and Drug Administration.

In the classroom at Brenham High School, with a 3D printer softly humming as it prints out a part for the Iron Man-themed hand, Hall straps on Kaedon’s green-and-white gift.

Kaedon watches curiously as Hall places it over his arm and attaches the Velcro strips. Once secure, Kaedon hugs Hall and gives him a high-five.

“Thanks for coming to see me, Kaedon,” Hall says.

Kaedon runs to his mom and hides his face behind her leg. On this day, Kaedon is a boy of few words in a crowded room of students who helped build his hand, but his smile says what words don't.

He peeks out from behind his mom’s leg and stretches out his arm, proudly showing off his new hand.