LUBBOCK, Texas — Many people have strong opinions about climate change and, at the same time, some are fuzzy on the facts.

So, I say, let’s go back to the beginning and understand what we know about climate change and how we know it.

Meet our guest

This summer I went on Facebook, asking viewers if they’d like to come along with me to report on the science of climate change.

I chose Justin Fain from Dallas.

“I need to sense, I need to see it, I need to feel it. If it's happening, I need to be shown this is what's happening,” Justin says.

He’s 38, a father of two and a roofing contractor. Justin is politically conservative and like most people in his social circle, he rejects the mainstream scientific conclusion that the planet is warming and humans are to blame.

So, together we're all going to explore three questions.

First, is the climate changing abnormally?

“No. Not from when I was a kid. My whole life time I haven’t seen anything different,” he says.

Next, are humans to blame?

“Do I think that people can change the climate? I don't think so. I don't think they can change what the world is doing,” Justin answers.

And, on a scale of 0-10 how urgent is it that we address this problem?

“I think this climate change is probably a three. Due to it's just a pattern in time,” he says.

Start from skepticism

The overwhelming majority of scientific papers conclude the climate is changing and people are to blame. Only a very small number of scientists disagree, John Christy is one of them. He's the state climatologist of Alabama.

“We're going to see scientists who say we are wrong,” Justin says, as we interview John over Skype.

“What questions should I ask them to have them prove themselves?” Justin asks.

“When you look at the evidence of ice melting in the arctic, just ask the question, ‘has the ice melted there before’? The answer is, absolutely yes. When they talk about sea level rise you can say, ‘has sea level risen before’? Absolutely yes,” John says.

“It's just not much effect, at all,” he adds.

“What are you picking up?” I ask Justin, as we wrap up our first interview.

“I'm picking up that I'm right,” Justin says with a laugh.

Carbon is climbing

We're headed to Texas Tech for Climate Change 101 with Professor Katharine Hayhoe, a climatologist.

While a meteorologist studies short-term weather patterns, a climatologist — like Katharine — studies 20-30 years of data to examine long-term trends.

The United Nations recently named her a UN Champion of Earth. She is also a co-author of the Fourth National Climate Assessment, a major report from NASA and 12 other U.S. government agencies.

“During the industrial revolution, what's the number one thing we did?” Katharine asks Justin.

“Burn coal,” he answers.

“The side effect is when you burn coal and gas and oil it produces carbon dioxide,” she says.

Katharine's telling us about carbon dioxide, or CO2. It's found naturally in the earth's atmosphere. As the sun's rays bounce off the planet, CO2 retains some of that heat. The rest escapes into space. When we add more carbon to the atmosphere that traps in more of the sun's heat.

“As far back as we can go in history, like I'm talking millions of years, we have no record of this much carbon going into the atmosphere, this fast,” she says.

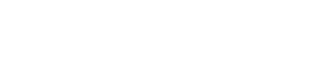

Data from NASA and NOAA show the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere goes up and down for 800,000 years but never above 300 parts per million. Around 1950 carbon levels start their rise to 400ppm.

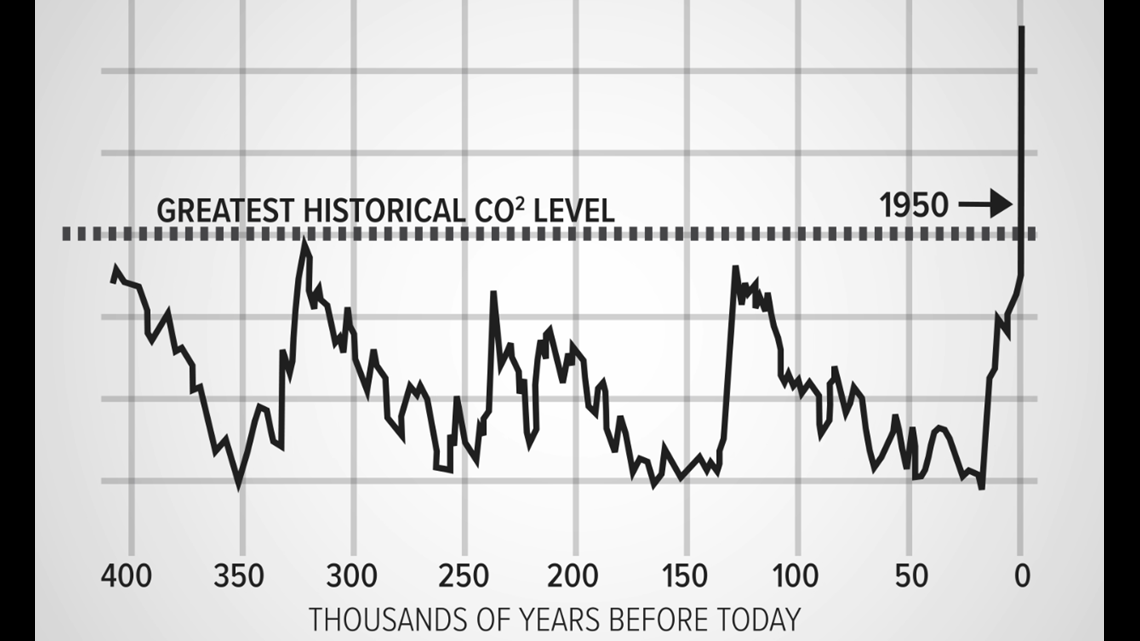

Now zoom into more modern times and you'll find CO2 rises just as global temperature also rises 1.5F.

Katharine says that’s having major effects.

“Here in Texas what we're definitely seeing heavy rainfall is getting more frequent,” she says. “Out here in West Texas we get droughts. And it turns out the hotter it gets the more intense our droughts are getting too,” she says.

“And of course, more extreme summer heat, as well,” Katharine adds.

As we wrap up our interview I circle back with Justin to his original assessment.

“Justin, out of 0-10 on urgency, was a three. What are you?” I ask her.

“Three or 4 years ago I would've been an eight. Now I think I'm a nine,” she says.

“Wow,” Justin says.

“I'm kind of like the doctor. I'm seeing the scans. The stuff we see is worse,” Katharine says. “If we wait until everybody in Dallas sees what I see already, it's going to be too late. So that's why it's so important to talk about this today,” he adds.

And what did Justin think of his time with Katharine?

“I’m looking at things a little different now. She gave me some information that never in my life would I hear,” he says.

Spelunking

We're north of Austin now at Innerspace Cavern in Georgetown with Jay Banner. He’s a geologist at the University of Texas and, like Hayhoe, a co-author of the Fourth National Climate Assessment.

“Alright when we get to the bottom of the tunnel, if you're taller than 5'7" watch your head. Or put your helmet on,” Jay tells us.

Jay is guiding us deep inside a cave because, while we did not have thermometers thousands of years ago, we did have caves. And they are one way we can tell what the climate used to be like. Other ways include things like tree rings, ice cores and marine sediments.

Shortly after entering the cavern complex Jay, Justin and I are on our hands and knees crawling through tight spaces.

“We're squeezing through. Trying to maneuver our bodies in such a way that I'd think my fat butt would get through there for minute,” Justin says.

I ask Jay what studying a cave can tell us about climate change.

“What the studies of caves can tell us about past climate are long-term changes. Changes we can't capture in the time we've been able to study climate through instruments. Rain gauges, thermometers, things like that. Those things go back 120 years or so,” he says.

He's telling us the dripping water in here creates the hanging formations called speleothems, also known as stalactites. On the inside they have these little rings that can tell us what the climate used to be like.

“One man's crime is another man's insight. You can see the rings, just like tree rings,” Jay says.

“Oh, yeah,” Justin says.

“You can see drops of water still coming through the center of these things,” Jay adds.

“I had no idea that's what it looked like inside,” Justin says.

From his research, Jay can infer periods in earth's history when carbon dioxide levels were on the rise in the atmosphere.

“You know those CO2 curves, how they go up from the 1970's to now? You can calculate that rate of change. You can calculate what we have from our past levels of CO2. And calculate those changes. The rate of change happening today is 40,000 times faster,” Jay says.

“So that's the difference. It's not the fact that it hasn't happened before, it's just the fact that its increasingly rapid now?” Justin says.

“That's right,” Jay says.

THE USUAL SUSPECTS

We're traveling to College Station to meet with Andrew Dessler. He's a climatologist at Texas A&M University and the author of two textbooks on climate change. He’s also active on Twitter, debunking the claims of those who are skeptical of the mainstream science of climate change.

To prove that carbon emissions from humans are the cause of climate change, it’s helpful to approach this like a criminal investigation, he says.

“Carbon dioxide has blood all over it. Blood of the climate system all over it,” Andy says.

“I like that analogy,” Justin says.

“And if you want to argue it's not CO2 not only do you have to advance a hypothesis, but you also have to say why does CO2 look so guilty,” he says.

Let's look at some of the usual climate change suspects:

- Is it the earth's orbit getting closer to the sun? No, Andy says that kind of change would take thousands of years.

- Is it the sun getting hotter? No. The sun is in a phase where it's generating less heat.

- Is it events like El Nino, which change the earth's weather patterns? Andy says there are no previous records that support these events causing long-term changes to the climate.

- So, that leaves carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses. Andy says the historical connection is strong between increased carbon and increased temperature.

“CO2 is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Not a shadow of a doubt. There's always a shadow of a doubt. But beyond a reasonable doubt there's really no question that we are responsible for the warming,” he says.

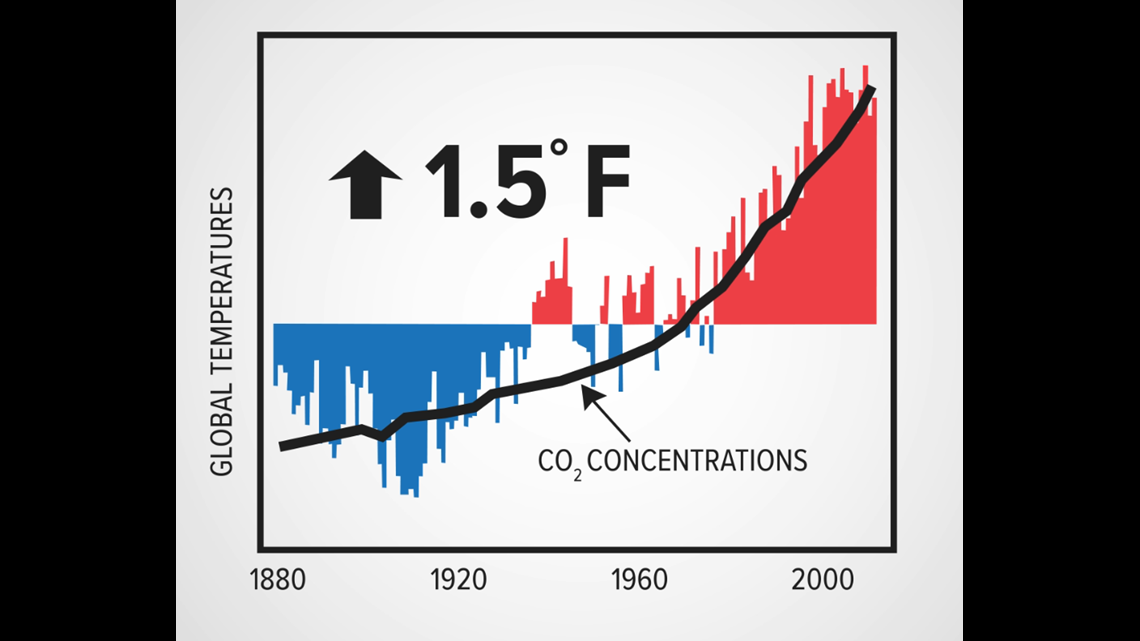

“Is there anything you can pinpoint, here in Texas, that you can go, this is a proof? This is what I'm talking about?” Justin asks.

“Probably the summer of 2011,” Andy says.

In Texas, the drier the summer, the hotter the temperature. And there are some hot and dry years. But nothing compares to the summer of 2011. There were 71 days above 100 degrees. That year, 301 million trees were killed in Texas.

This report says, because of climate change, extremely hot summer days are now 10 times more likely.

“We’ll still have average years, still have cool years. But when you have a hot year it's going to be worse,” he adds.

“It's like, if someone hit 200 homeruns. You almost certainly expect them to be doping. The climate is doping,” Andy says.

Conclusion

So, we learned the earth's climate has changed before but this is different. In a matter of decades we've spiked the atmosphere with carbon — and other greenhouse gases — and that's causing the temperature on earth to rise.

But what's Justin thinking?

“Am I convinced yet on an actual real problem? The jury is still out,” he says.

Justin's not convinced. But this journey's not over. Next, we're going to Alaska so he can see the effects of climate change for himself.

Watch this series on YouTube here:

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Got something you want verified? Send David an email: david@verifytv.com

Explore other Verify stories using the map below.