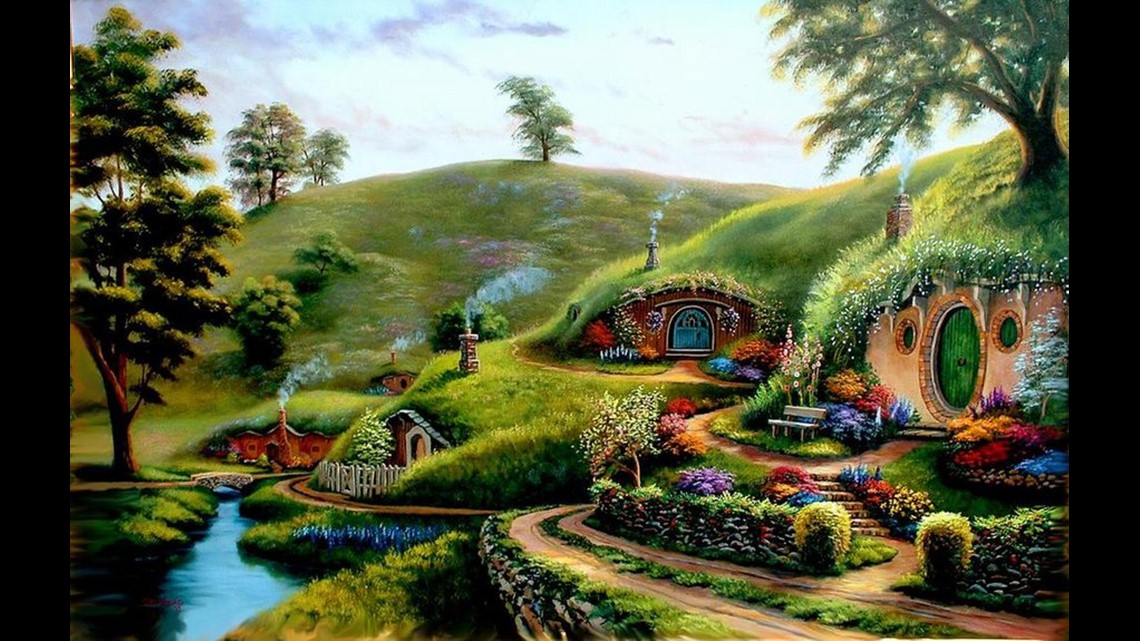

HOUSTON — For me the idea of working with nature instead of against it taps carnal instincts, embedded deep in the psyche. Finding shelter in a dangerous world full of lions ready to pounce can release endorphins and make you feel alive! Where best to seek refuge? A cave? A hillside? A quick look back at ancient times reveals entire civilizations doing just that: reference Mesa Verde in Arizona.

In other parts of the world and in popular fantasy, the idea of living in an underground layer (like Hobbits do in, "Lord of the Rings") is attractive because it provides the best defense from hot sunshine and cold winter winds. Earth provides natural insulation to keep the home comfortable with little energy needed. While the reality is that a subterranean dwelling like this exists mostly in our imaginations -- the lower maintenance and overall quiet would provide a huge relief from the busy suburban weekend life of growling lawnmowers, roaring leaf-blowers and buzzing weed-whackers. Going with nature instead of against it would also satisfy that aforementioned instinctual human desire to go with nature!

Now, I’m not suggesting we all dig a hole and live a feral life in the forest, but one way to approach the concept of symbiosis with nature is by using ivy! Here's where I sell you on the idea that ivy is actually GOOD for your house and here's where some of you will scoff at me for even going there. But stay with me: not all ivy is created equal -- at least in the application of our enhancing our homes.

The fear with all vines and reason when you search it online you'll see many, "home advice" sites discouraging its use, is that it'll take over your home and your yard. They say some ivys will rip apart your home's brick or wood siding and be a general nuisance. You know what? They're right. But, they're only right for some varieties -- and I'd never encourage you to plant those. But, ivy is alive and like anything worth it (like your lawn), ivy takes work. In this case you must occasionally trim it back and if you have a multi-story house or building this might include using a ladder or employing the wares of a lawn service.

My choice of ivy for Texas? Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia). A deciduous vine, it loses its leaves during the winter but features a delightful canopy of shade-providing green foliage in the spring and summer. In autumn, it turns wild shades of yellow and red. Here’s where the symbiosis comes in: If growing on the side of a home or building, it'll block the solar rays that heat up your structure during the warm months, saving on cooling bills. In winter when it's bare allowing warming sunshine to splash down, saving you on heating costs. That's sounding better!

Many will agree that beyond its utilitarian function, ivy is also quite beautiful. Whether it's a charming townhouse in Ireland or an, "Ivy League" college in America, ivy adds a touch of class to any plain-looking home or building.

Some who've never been exposed to Virginia Creeper may see it as poison ivy. But unlike that itchy fest of a vine, the whimsical, winding vine of Virginia Creeper features leaves with five fingers, instead of three. ("Leaves of three, let them be... Leaves of five, let them thrive!") Virginia Creeper will not cause an allergic blistering like poison ivy, though like many ornamental plants its berries are poisonous to all but birds. One great thing about Virginia Creeper is that if you are ready to part ways, its suction cups are easily removable from the structure and a quick power-wash will remove all vestiges of the plant. One more tip: Virginia creeper like other vines, can spread horizontally through runners below ground and emerge up to 25 feet away to climb on other surfaces. Because of that, many have vilified this otherwise beneficial plant because it'll pop up unexpectedly along a fence line. You may have to beat it back at times. (To kill the plant for good, the roots should be treated with Round Up, so it doesn't sprout up at a later date from runners in the ground.)

Virginia Creeper should also not be confused with, "Creeping Fig." (Ficus pumila) Popular in Houston, that vine creates a thick and uniform covering but it's evergreen, so provides no wintertime benefit, and does have tendrils which will eat away at brick stucco and go under wooden siding and its roots can crack a foundation if the plant has been there for more than a decade. For the long-term health of a structure using creeping fig is discouraged due to its damaging potential, though due to it's highly trainable nature (you can make it conform to shapes) and it's ability to cover entire walls in a uniform way, the vine's aesthetically popular and found in many affluent neighborhoods throughout Houston.

Unlikely creeping fig, Virginia Creeper can wilt a little bit during Houston's hottest months if 100% sun-exposed during the afternoon, but with ample water it should be fine. It also grows much, much faster than climbing fig and after just three years entire wall can be covered and what would take climbing fig triple time. Again, consider the speed of achieving this shade benefit in such a short time, compared to that of a much slower-growing shade tree. It could take a decade for a tree to reach that shade potential.

Because this blog may be read in places other than Texas, be sure to check with your local laws before planting, as it could be considered an invasive species where you live. English ivy is a prime example: it is wildly popular but can also spread aggressively and is tough to eradicate and is considered a pest.

So, what do you think? Is it the solution you've been looking for, or does it sound like more work than you'd want to take on? -Meteorologist Brooks Garner