This story is part of KHOU 11 Investigates' series “Unforgivable.” Parts may contain graphic descriptions of sexual assault. If you or a loved one have experienced sexual abuse, get help through the free and confidential National Sexual Assault Hotline (1-800-656-HOPE).

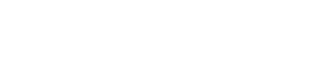

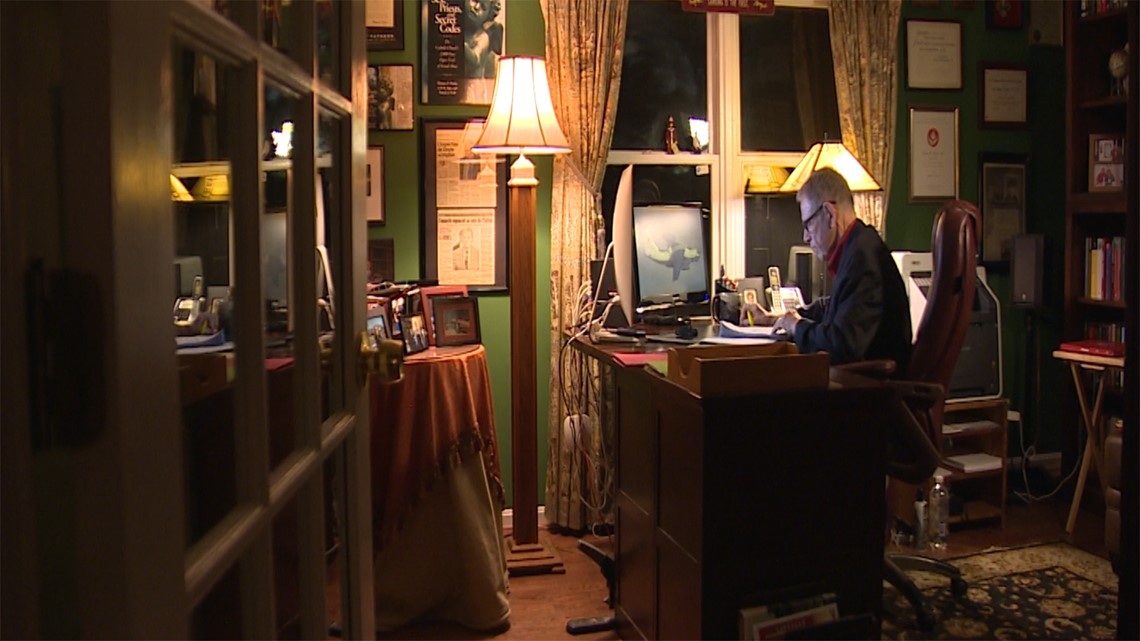

The dark green walls of Rev. Thomas P. Doyle’s home office are barely visible beneath mementos of his life’s work: five master’s degrees, a doctorate in Canon Law, photos and framed newspaper articles with headlines that read, “Vatican Declined to Defrock U.S. Priest Who Abused Deaf Boys.”

The sun’s already gone down in the wooded Washington, D.C. suburb Doyle calls home. But Doyle, 74, is still working. He thumbed through a stack of articles about clergy sex abuse, something he does a few times a week in between keeping up with cases in which he’s a consultant or expert witness.

“Most of my adult life has been involved with this issue. It’s changed me dramatically. It’s changed my belief system,” Doyle said. “I no longer have any trust in the institutional church. None whatsoever.”

For more than 30 years, Doyle has reviewed over 1,000 clergy sex abuse cases around the world. He rattled off the countries in which he’s worked — the U.S., Ireland, England, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Belgium and Brazil.

His years of experience led him to conclude that a solution will only come from more accountability from church leadership.

“The common theme that I have seen in every country where I have encountered this, on this planet, over 34 years, has been this — the bishops have tried to conceal and lie about the issue,” Doyle said.

Eroding trust

That trust started to erode about 35 years ago, not far from his colonial home tucked in a cul-de-sac at the end of a winding road. Just on the other side of the Potomac River, Doyle served as a canon lawyer in the 1980s at the Vatican embassy in Washington.

Part of his job was reviewing sex abuse files from across the country. That’s when a case from South Louisiana landed on his desk.

Doyle knew sex abuse was an issue in the church, but this case was different. Gilbert Gauthe, a priest in the Diocese of Lafayette, abused at least 100 children in the 1970s and '80s and was convicted of child molestation in 1985.

“As that started, I realized after talking with the people in Louisiana, this was — this was a bigger problem than we imagined,” Doyle said. “I never encountered something like this before, directly.”

Once the Gauthe case became public, other survivors began coming forward when they never had before. Doyle heard from families who previously thought their case would fall on deaf ears or didn’t believe their children until they realized they weren’t alone.

“I had no idea how widespread it was,” Doyle said. “What I really had no idea about was how the institutional church — the bishops — would react.”

The same year Gauthe was convicted, Doyle warned bishops a “real present danger exists” in the church in his groundbreaking 90-page report, “The Problem of Sexual Molestation by Roman Catholic Clergy.”

He outlined how sex abuse allegations should be handled and warned what happened in the Gauthe case shouldn’t be repeated — what he now calls “the most common solution" — to quietly transfer an accused priest to another parish.

“I naïvely thought that once we presented them with this information that they would immediately get together and do something to stop it. You know, they’d reach out to the victims and do something about the perpetrators,” Doyle said. “I was totally wrong.”

Instead, the church hierarchy dismissed his report, telling him they already knew everything that was in it and already had a policy for dealing with it; the policy just wasn’t written down.

Soon after, Doyle was let go from his embassy job. He’s been an inactive priest ever since.

His former boss once told him, “If you want to have a career, you have to put this stuff behind you,” Doyle said.

“I couldn’t in conscience, because I had met victims and that changed everything for me,” Doyle said. “Once I met some of the victims, especially the younger ones, it changed my life, knowing what had happened to them. I met some kids who were 11, 12 years old and I also saw the medical reports, and they were appalling.”

Wake-up calls

An outspoken cleric, Doyle was thrown into a life devoted to fighting for those survivors and fighting against the church’s handling of the crisis.

When he was first asked to serve as an expert witness in 1988, he didn’t even know what that was. Now he’s lost count of how many times he’s testified.

Throughout the years, he’s worked on major cases that he thought would be a wake-up call. In 1997, he was an expert witness in a Dallas case that garnered a $119 million verdict, the largest ever against the Catholic Church. Since the 1980s, U.S. Catholic dioceses and religious institutes have paid more than $3 billion to settle lawsuits about sexual abuse, according to BishopAccountability.org, an online database of the sex abuse crisis.

“There have been several wake-up calls,” he said. “The myth is that the institution, the bishops are going to be able to fix themselves. … They haven’t fixed it; they’ve made it worse, because, in trying to fix it, they’ve actually gone deeper into the dishonesty, into hiding and into the lying. It’s systemic.”

Throughout the years, Doyle said he has seen policies that prohibit priests from showing sympathy to survivors who disclose abuse to them. He said another sent accused priests to psychological evaluation and reinstated them unless they were diagnosed as a pedophile or admitted to the abuse.

He said he’s watched bishops only consider forced penetration as sexual abuse and use euphemisms like “inappropriate boundary issues,” “inappropriate behavior,” “misplaced affection,” “morally questionably behavior” or “overly aggressive affection” to dismiss claims.

‘Nothing changes’

Some steps to end abuse have been taken over the years, but Doyle points to a paramount issue that hasn’t been addressed — bishop accountability.

In 2002 in Dallas, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops passed the “Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People.”

It established zero tolerance for abusive priests and deacons, including reporting abuse to police. But the charter does not include consequences for bishops who conceal abuse. The bishop conference has revisited the charter over the years and made minor changes, but it took until 2018 for the bishops to look inward.

“Brother bishops, to exempt ourselves from these high standards of accountability is unacceptable and cannot stand. In fact, we, as successors to the apostles, must hold ourselves to the highest possible standard. Doing anything less insults those working to protect and heal from the scourge of abuse,” Cardinal Daniel DiNardo said at the opening of the conference’s general assembly in November.

But the strong words from DiNardo, the president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and leader of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston, came just hours after a vote to make bishops more accountable was put on hold at the request of the Vatican.

“And nothing changes, and that’s what makes the victims furious,” Doyle said. “They’re sick and tired of all of it. They want action.”

In his 2006 book, “Sex, Priests and Secret Codes,” Doyle traced the history of clergy sexual abuse of children to A.D. 98, the same century the church was founded.

“The Roman Catholic Church, the leadership, the bishops, the popes, have been well aware of this issue for the entire duration of the church’s existence,” Doyle said.

He’s lost all faith in the bishops’ ability to fix the issue themselves.

“It’s like having Hitler take care of the problem of anti-Semitism among the SS. That’s how much sense it makes,” Doyle said. “There is not the will to fix it. The only will there is, collectively, is to protect the image of the institution.”

Call for transparency

There are more than 19,000 people who survived abuse by U.S. priests from 1950 to July 2017, according to a BishopAccountability.org analysis of U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops data.

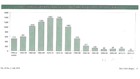

Although hundreds of allegations are made every year, most of the actual abuse happened in the 1960s, '70s and '80s, according to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University. The Galveston-Houston Archdiocese pointed to that data, which showed a decline in recent incidents.

“The Dallas Charter reforms from 2002 have clearly had a material, positive impact in addressing this evil,” the archdiocese said in a statement.

And recently, DiNardo has vowed to do more to rectify past “moral failures.” A KHOU analysis of his statements since September 2017 found at least nine instances of DiNardo vowing to improve accountability and transparency.

“Both the abuses themselves, and the fact that they have remained undisclosed for decades, have caused great harm to people’s lives and represent grave moral failures of judgment on the part of Church leaders,” he said in an Aug. 1, 2018 statement.

The closest the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston has come to disclosing its abuse accusations was 15 years ago. Then-Bishop Joseph Fiorenza wrote in a letter to the faithful that 22 priests and four deacons had “sustainable accusations” in the previous 53 years. But that did not include names.

Then in October, DiNardo announced that his archdiocese would do something it's never done before: publicly name priests “credibly accused” of sexually abusing children.

“This is an action in response to the faithful’s call for greater accountability and transparency,” DiNardo wrote in an Oct. 10, 2018 letter. “Every bishop in our state has made a statement expressing his concern for all who have been hurt and I want to express my personal sorrow at such fundamental violations of trust that have happened.”

But Doyle said he’s heard this rhetoric before and needs more action to believe them.

“They’ve been saying that for 20 years. They’re still not transparent. They pick and choose when they want to be transparent,” he said. “And all the promises of transparency, of caring for the victims, that’s the biggest farce. When they’re talking about, ‘We’re gonna do everything we can; they’ll be our biggest priority.’ Well, they haven’t been yet.”

He questioned the accuracy of the list the dioceses will release, because it’s based on which accusations bishops deem are credible. He said he’s seen instances where a diocese will release a shortlist of accused priests when the real number is three times as high.

That happened as recently as December when the Illinois Attorney General found the state’s diocese failed to disclose sexual abuse allegations against 500 clergy. They fell through the crack because 74 percent of all allegations the dioceses received were not deemed credible, sometimes because they were never investigated.

“What’s happened in a lot of these so-called investigations, they’ll go to the priest and confront him, and if he says, ‘No, I didn’t do it,’ they’ll believe him and that’s the end of it,” Doyle said. “The only way you’re going to get a true picture is when an outside agency that has the expertise and the time and the commitment. And the district attorneys do, to go through all of this and come up with a credible number.”

In a statement, the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston said a “highly respected, independent consultant” was given “unfettered access to archdiocese records to help produce a list of priests credibly accused of sexually abusing a minor going back to 1950.”

The archdiocese wouldn’t go into detail about how it will define a credible accusation, nor would it grant an interview with DiNardo. Since September, KHOU 11 Investigates has requested an interview with DiNardo 11 times.

Doyle called the term “credibly accused” a “subjective definition.”

“That the institution, the bishops are coming up with because of the pressure they’re under, to do something,” he said. “The bishops who are, in a sense, deciding this for the church, they’re all celibate males who’ve never been married, have never been a parent. They don’t have a clue what a parent feels like when they find out their child has not only been sexually violated, but it’s by a priest whom they’ve trusted with their whole life. They don’t have a clue what that’s like.”

‘I’m sorry’

Doyle has made it a point to simply listen and offer his sympathies to survivors over the years.

“I just let them talk. When the victims, when they’ve told their story, I’m able to say, ‘I’m a cleric. I’m still in the system, so I want to tell you how sorry I am for what we did to you and to your family to your parents. How sorry I am, because there’s no excuse for it,’” he said.

Those simple words — “I’m sorry for the pain you’ve gone through. I’m sorry it’s been hurtful.” — have meant so much to survivors, he said.

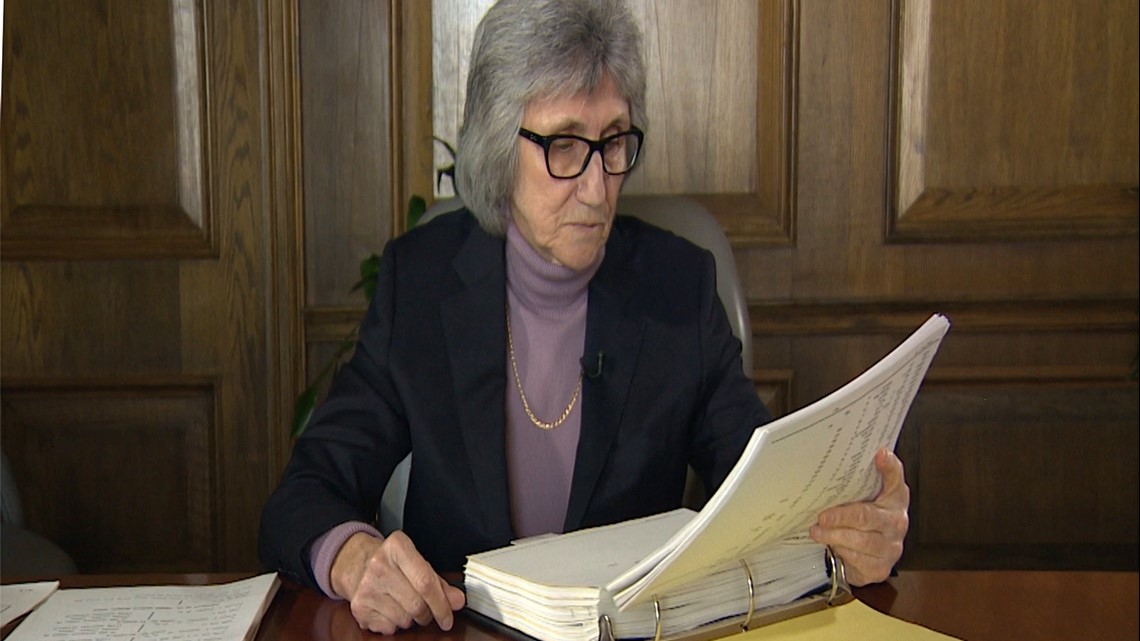

Back in 1997, Doyle worked with attorney Sylvia Demarest in the Dallas case that received a $119 million verdict. During the trial, she became frustrated when she couldn’t find him. When she did, he was in the hallway, surrounded by survivors.

“And I later found out that what he was doing was he was apologizing to them … doing what a priest should do, which is to minister to those who are hurting,” Demarest said. “No one within the church had ever apologized to them.”

Later, her clients told her how important that was to them. Doyle received a standing ovation in that case, and that kind of validation that he’s helping victims, keeps him going.

It helped him through a threat of excommunication and his early doubts of whether he was doing the right thing.

“I went through a long, fairly painful discernment process myself,” he said. “I began to believe sometimes people saying, ‘You’re destroying the church. You’re breaking down the church.’ I said, ‘No, I’m not. I’m trying to help it by helping to do the right thing with all these people that we’ve violated.’”

Although he hasn’t been an active priest for 30 years, vestiges of Doyle’s faith still adorn his office wall. At least half a dozen crosses hang between diplomas and letters. Among them, a cross engraved with the Serenity Prayer, “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can and the wisdom to know the difference.”

“This is the reality I live in,” Doyle said. “Seeing the same thing day after day, hearing the same stories, the same excuses, the same lies, day after day after day, week after week, year after year without any change.”